Learn, Solve & Master Python, Linux, SQL, ML & DevOps

🐧 Linux The Foundation for Every Developer

🚀 Learn Linux the Right Way – Practical, In-Depth & RHCSA-Focused

Master Linux from the ground up, from basic commands and system navigation to advanced administration, networking, automation, and security.

These tutorials are designed for real-world learning and complete RHCSA exam preparation.

⬇️ Jump To

Introduction to Linux

Linux is a free, open-source operating system that powers everything from mobile devices to servers and supercomputers. It provides a stable, secure, and efficient platform for both personal and enterprise use.

Why Learn Linux?

It’s the backbone of cloud, DevOps, and server administration.

Used by major companies: Google, Amazon, Red Hat, IBM, and more.

Essential for certifications like RHCSA, RHCE, and LFCS.

Key Features

Multi-user and multi-tasking support

Open-source and customizable

Secure and stable

Community-driven development

💡 Pro Tip: Learning Linux gives you the foundation for working with any modern technology stack, from development to deployment.

Linux Architecture Overview

The Linux operating system is structured in layers, each with a specific role in how it operates.

Hardware ⮕ Kernel ⮕ System Libraries ⮕ Utilities ⮕ User Space

Here’s a simplified breakdown of its main components:

| Layer | Description |

|---|---|

| Hardware | The physical components: CPU, memory, disks, and devices. |

| Kernel | The brain of Linux: manages hardware, memory, and processes. |

| System Libraries | Provide functions that interact with the kernel (e.g., glibc). |

| System Utilities | Core tools for managing files, processes, and users. |

| User Space | Where applications and user commands run. |

💡 Pro Tip: The kernel is like a bridge between your hardware and software, it ensures they talk efficiently.

Linux Distributions

Below are some of the most popular Linux distributions widely used across different environments:

Ubuntu: Beginner-friendly and ideal for newcomers, developers, and desktop users.

Fedora: Known for its cutting-edge features and frequent updates.

CentOS Stream: A rolling-release model that tracks just ahead of RHEL.

RHEL (Red Hat Enterprise Linux): Enterprise-grade, stable, and widely adopted in production environments; essential for RHCSA/RHCE certifications.

AlmaLinux: A free, open-source, 1:1 binary-compatible alternative to RHEL, popular after CentOS transitioned to Stream.

Debian: Renowned for its stability, strong community support, and long-term reliability.

💡 Pro Tip: If you’re preparing for RHCSA, focus on RHEL or AlmaLinux, since both share the same commands, structure, and package management system

Accessing the Command Line in Linux

Bash Shell

The Bash (Bourne Again Shell) is the default command-line interface in most Linux systems, used to execute commands, run scripts, and automate administrative tasks.

[user@host ~]$ → Shell Prompt

[user@host ~]# → Superuser Shell Prompt

Login using SSH

SSH (Secure Shell) is a protocol used to securely connect to a remote Linux system over a network. It encrypts all communication, protecting passwords and commands from eavesdropping.

ssh username@remotehostusername→ the user account on the remote systemremotehost→ the hostname or IP address of the remote system

For added security, you can use SSH keys instead of passwords (Click here for more details on SSH Keys):

ssh -i /path/to/private_key username@remotehost-i /path/to/private_key→ specifies your private key fileThe matching public key must be added to the remote user’s

~/.ssh/authorized_keys

Host Verification

The first time you connect to a remote host, SSH may prompt:

The authenticity of host 'remotehost (IP)' can't be established. Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no)?Enter

yesto accept the host key and save it for future connections.

Security Tip

- Never share your private key.

- Use

chmod 600 mykey.pemto restrict access to your key file.

Logout

To safely end your session, type:exit

or press Ctrl + D.

💡 Pro Tip: Using SSH keys is highly recommended for servers and cloud instances, especially for RHCSA exam practice and real-world setups.

Basic Linux commands and Shortcuts

This section introduces some of the most commonly used Linux commands and Bash shortcuts that every user should know.

Common Commands

whoami→ Displays the current logged-in usernamecommand1; command2→ Executes multiple commands sequentiallydate→ Displays the current date and timedate +%R→ Displays the time in HH:MM format (+%Ris a string formatter)date +%x→ Displays the current date in MM/DD/YYYY format (+%xis a string formatter)passwd→ Changes or sets the user’s passwordfile <file_name>/<directory_name>→ Determines and displays the type of file or directory

Viewing File Contents

cat <file_name>→ Displays the content of a filecat <file_name1> <file_name2>→ Displays the contents of multiple files sequentiallyless <file_name>→ Views long files page by page (use ↑ / ↓ keys to scroll, andQto exit)head <file_name>→ By default, displays the first 10 lines of a filehead -n 15 <file_name>→ Displays the first 15 lines of a file. The number 15 can be replaced with any numbertail <file_name>→ By default, displays the last 10 lines of a filetail -n 20 <file_name>→ Displays the last 20 lines of a file. The number 20 can be replaced with any number

Counting File Data

wc <file_name>→ Counts lines, words, and characters in a filewc -l <file_name>→ Counts only the number of lineswc -w <file_name>→ Counts only the number of wordswc -c <file_name>→ Counts only the number of characters

Command History and Continuation

history→ Displays a list of previously executed commands!ls→ Repeats the most recent command starting with “ls”!<number>→ Executes the command corresponding to that number from the history (e.g.,!25)

Command Continuation

When a command is too long to fit on one line, you can use a backslash (\) at the end of the line to continue typing on the next line.

This improves readability and organization in scripts or complex commands.

Always make sure there’s no space after the backslash, or the continuation won’t work.

-

head -n 3 \> /usr/share/dict/words \> /usr/share/dict/linux.words

Other Useful Commands

man -k <keyword/command>→ Searches the manual (man) pages for a given keyword or commandmkdir -p Thesis/Chapter1 Thesis/Chapter2 Thesis/Chapter3→ Creates multiple parent and subdirectories at once

Tab Completion

Tab completion helps you quickly complete commands or file names by pressing the Tab key.

-

- Press Tab once → Auto-completes if the command or file name is unique.

- Press Tab twice → Shows all possible matches.

Useful Command-line Editing Shortcuts

| Shortcut | Description |

|---|---|

| Ctrl + A | Jump to the beginning of the command line. |

| Ctrl + E | Jump to the end of the command line. |

| Ctrl + U | Clear from the cursor to the beginning of the command line. |

| Ctrl + K | Clear from the cursor to the end of the command line. |

| Ctrl + ← (Left Arrow) | Jump to the beginning of the previous word on the command line. |

| Ctrl + → (Right Arrow) | Jump to the end of the next word on the command line. |

| Ctrl + R | Search the history list of commands for a matching pattern. |

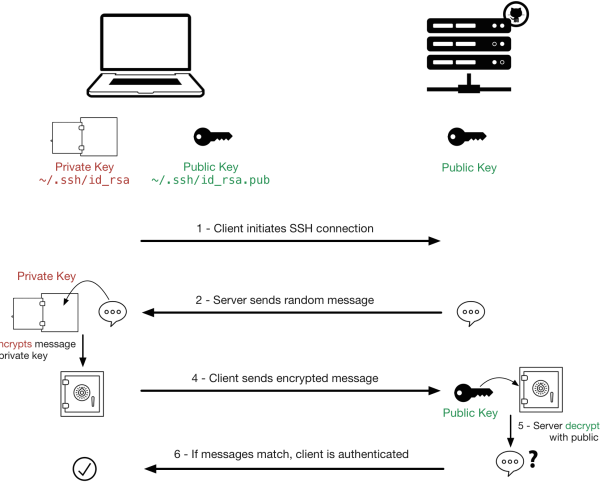

SSH Key-Based Authentication

SSH key-based authentication is a more secure and convenient way to log in to remote systems without using passwords.

Instead of typing your password each time, a pair of cryptographic keys (a public key and a private key) is used to establish trust between the client and the server.

The private key acts as your authentication credential and must be kept secret and secure, just like a password.

The public key is copied to the remote system you want to access and is used to verify the private key. It does not need to be confidential.

Generating SSH Keys

To create a private key and matching public key for authentication, use the ssh-keygen command.

[user@host ~]$ ssh-keygen Generating public/private rsa key pair. Enter file in which to save the key (/home/user/.ssh/id_rsa): Enter Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase): Enter Enter same passphrase again: Enter Your identification has been saved in /home/user/.ssh/id_rsa. Your public key has been saved in /home/user/.ssh/id_rsa.pub.~/.ssh/id_rsa→ Private key~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub→ Public key

If you set a passphrase, you’ll need to enter it when using the key. Else, anyone with your private key file could use it.

Example: Custom Key Name with Passphrase

[user@host ~]$ ssh-keygen -f ~/.ssh/key-with-pass Generating public/private rsa key pair. Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase): Enter same passphrase again: Your identification has been saved in ~/.ssh/key-with-pass Your public key has been saved in ~/.ssh/key-with-pass.pubThe

-foption lets you specify a custom filename.The example above creates a passphrase-protected key pair:

~/.ssh/key-with-pass→ Private key~/.ssh/key-with-pass.pub→ Public key

Sharing the Public Key

ssh-copy-id command copies the public key of the SSH keypair to the destination system.ssh-copy-id -i .ssh/key-with-pass.pub user@remotehost→ Copies the specified public key to the remote host.ssh-copy-id user@remotehost→ Copies the default public key (~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub) to the remote host.ssh -i .ssh/key-with-pass user@remotehost→ Uses the specified private key to connect.ssh user@remotehost→ Uses the default private key (~/.ssh/id_rsa) to connect.

SSH-agent

When using SSH keys protected with a passphrase, you normally need to enter it each time you connect.

To avoid this, you can use ssh-agent, which securely stores your private key’s passphrase in memory, allowing you to enter it only once per session.

eval "$(ssh-agent -s)"→ Start the agentssh-add ~/.ssh/id_rsa→ Add your key (enter passphrase once)ssh user@remotehost→ Login without re-entering it

Identifying Remote Users

[user01@remotehost ~]$ w

16:13:38 up 36 min, 1 user, load average: 0.00, 0.00, 0.00

USER TTY FROM LOGIN@ IDLE JCPU PCPU WHAT

user02 pts/0 172.25.250.10 16:13 7:30 0.01s 0.01s -bash

user01 pts/1 172.25.250.10 16:24 3.00s 0.01s 0.00s wColumn descriptions:

USER: Logged-in username

FROM: Remote IP address

IDLE: Idle time

WHAT: Current command being executed

SSH Host Keys

When connecting to a server:

The client checks the server’s public key against its local known hosts file.

If the key is unknown or changed, the user is prompted for confirmation.

Once accepted, the key is stored in

~/.ssh/known_hosts.

Example:

[user01@host ~]$ ssh newhost

The authenticity of host 'newhost (172.25.250.12)' can't be established.

ECDSA key fingerprint is SHA256:qaS0PToLrqlCO2XGklA0iY7CaP7aPKimerDoaUkv720.

Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no)? yes

Warning: Permanently added 'newhost,172.25.250.12' (ECDSA) to the list of known hosts.SSH Known Hosts File

Public keys of remote servers are saved in:

System-wide:

/etc/ssh/ssh_known_hostsUser-specific:

~/.ssh/known_hosts

Each entry includes:

<hostname> <key_algo> <public_key>Example entry from ~/.ssh/known_hosts:

remotehost,172.25.250.11 ecdsa-sha2-nistp256 AAAAE2VjZH...

If a server’s key changes (due to reinstall or rotation), remove its old entry from this file to avoid SSH warnings.

Configuring the OpenSSH Server

The OpenSSH server is managed by the sshd daemon. Its main configuration file is:

/etc/ssh/sshd_configIt’s generally used with secure defaults, but two common security enhancements are:

- Prohibit Remote

rootLogin- Reason to disable root SSH login:

- Reduces attack surface (root is a known username).

- Avoids misuse of root’s unrestricted privileges.

- Improves accountability (users must log in as themselves first).

- To disable root login:

- Edit

/etc/ssh/sshd_config:PermitRootLogin no

- To allow only key-based root login (optional):

PermitRootLogin without-password

- PermitRootLogin without-password

sudo systemctl reload sshd

- Edit

- Reason to disable root SSH login:

- Disable Password-Based Authentication

Benefits of key-based authentication:

Prevents brute-force password attacks.

Safer if private keys are passphrase-protected.

Can use

ssh-agentfor convenience.

- To disable password authentication:

- In

/etc/ssh/sshd_config:PasswordAuthentication no

Then reload SSH:

sudo systemctl reload sshd

- In

💡 Pro Tips:

The permission modes must be 600 on the Private Key, 644 on the Public Key, and 600 for Authorized Keys

chmod 600 ~/.ssh/id_rsa→ Private Key Permissionchmod 600 ~/.ssh/authorized_keys→ Authorized Keys Permissionchmod 644~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub→ Public Key Permission

When you run the ssh-keygen command again without changing the filename of the existing keys, the old keys are overwritten with new ones. As a result:

- The old public key previously shared with a server is no longer valid.

- You will not be able to log in to that server using the new private key.

- To fix this, you must copy the new public key again to the remote server using the

ssh-copy-idcommand

Before disabling password-based authentication, ensure that every user already has their public key added to the server’s ~/.ssh/authorized_keys file, otherwise they will be locked out of SSH access.

Managing File Systems

On Linux, all files are organized in a single inverted tree called the file-system hierarchy, with / as the root directory.

Subdirectories like /etc and /boot help organize files by type and purpose.

Files and directories are referenced using / as a separator, e.g., /etc/issue refers to the issue file inside /etc.

| Location | Purpose |

|---|---|

| /usr | Installed software, libraries, include files, and read-only program data. Important subdirs: /usr/bin (user commands), /usr/sbin (admin commands), /usr/local (local software). |

| /etc | System-specific configuration files. |

| /var | Variable data that persists across boots, e.g., databases, logs, cache, and website content. |

| /run | Runtime data for processes since last boot, including PID and lock files. Recreated on reboot. |

| /home | Home directories for regular users’ personal data and configs. |

| /root | Home directory for the administrative superuser, root. |

| /tmp | Temporary files. Auto-deleted if not used for 10 days. /var/tmp retains files for 30 days. |

| /boot | Files required for system boot. |

| /dev | Special device files used to access hardware. |

Basic Linux Commands You Should Know

pwd→ Prints current directory.ls→ Lists all files and directories in the current directory.

Note: All ls variations (-l, -la, -R) support specifying one or more directories, e.g., ls /etc /var.

ls -l→ Shows files in long listing format with details like permissions, owner, size, and modification date.ls -la→ Lists all files including hidden files (those starting with.).ls -R→ Recursively lists all files in the current directory and its subdirectories.

cd <directory_path>→ Changes the current directory.cd ..→ Moves up one level to the parent directory.cd -→ Changes back to the previous directory.touch <file_name>→ Updates a file’s timestamp to the current date/time or creates an empty file if it doesn’t exist.

Command-line File Management

To manage files and directories effectively, you can use various commands to create, remove, copy, move, and organize them.

Creating Directories

mkdir <directory1> <directory2>→ Creates one or more directories.mkdir -p <directory1> <directory2>→ Creates parent directories if they don’t already exist.- Example:

mkdir Videos/Watchedmkdir -p Thesis/Chapter1 Thesis/Chapter2 Thesis/Chapter3

Copying Files

cp <filename> <new-filename>→ Copies a file and creates a duplicate with a new name.cp -r <directory> <new-directory>→ Copies an entire directory recursively (all files and subdirectories).If the destination already exists, it will be overwritten.

- Example:

cp blockbuster1.ogg blockbuster3.oggcp -r Thesis ProjectX

Moving Files

mv <filename> <new-filename>→ Moves or renames a file.mv <directory> <new-directory>→ Moves or renames a directory.- Example:

mv thesis_chapter2.txt thesis_chapter2_updated.txtmv Chapter1 Thesis/Chapter1_updated

Removing Files and Directories

rm <filename1> <filename2>→ Removes one or more files.rm -r <directory1> <directory2>→ Removes directories and their contents recursively.Use

-ifor confirmation before each file.Use

-fto force deletion without prompts.

rmdir <directory1> <directory2>→ Removes empty directories.- Example:

rm thesis_chapter2_updated.txtrm -rf Chapter1_updatedrmdir Chapter1

Managing Links Between Files

It’s possible to create multiple names that point to the same file through Hard Links and Soft (Symbolic) Links.

Hard Links

A Hard Link is another name that points directly to the same file data.

Even if the original file is deleted, its contents remain available through the hard link.

Hard links cannot be created for directories.

Hard links must be on the same file system.

ln newfile.txt /tmp/newfile-hlink2.txt→ Command to create hard linkln→ Command used to create a hard linknewfile.txt→ Original file/tmp/newfile-hlink2.txt→ Hard link name

To verify both files point to the same data:

[user@host ~]$ ls -il newfile.txt /tmp/newfile-hlink2.txt 8924107 -rw-rw-r--. 2 user user 12 Mar 11 19:19 newfile.txt 8924107 -rw-rw-r--. 2 user user 12 Mar 11 19:19 /tmp/newfile-hlink2.txtThe same inode number confirms both are hard links to the same file.

- When to use:

You want multiple filenames for the same file on the same file system.

You need backup-like access without extra storage.

Soft (Symbolic) Links

A Soft Link (also called a Symbolic Link) is a special type of file that points to another file or directory.

Can link files across different file systems.

Can link to directories or special files, not just regular files.

If the original file is deleted, the soft link remains but becomes a “dangling link” (A Soft link pointing to a missing file).

ln -s /home/user/newfile-link2.txt /tmp/newfile-symlink.txt→ Command to create soft linkln -s→ Command used to create a soft (symbolic) link/home/user/newfile-link2.txt→ Original file/tmp/newfile-symlink.txt→ Soft link name

- When to use:

You want a shortcut to another location.

You’re linking across partitions or to a directory.

You frequently manage system files, logs, or scripts from one place.

Command-Line Expansions

The Bash shell supports several kinds of expansions that simplify command-line operations. These include pattern matching (globbing), home directory expansion, string and variable expansion, and command substitution.

Pattern Matching (Globbing)

- Globbing expands wildcard patterns into matching file or path names. These metacharacters help you perform operations on multiple files efficiently.

| Pattern | Examples | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| * | ls a* → matches able, alfa ls *a* → matches able, baker, charlie | Matches any string of zero or more characters. |

| ? | ls ?.txt → matches a.txt, b.txt ls a? → matches ab, ax | Matches exactly one single character. |

| [abc…] | ls [ab]* → matches able, baker ls [ch]* → matches charlie, henry | Matches any one character from the specified set inside brackets. |

| [!abc…] or [^abc…] | ls [!a]* → matches everything except files starting with a ls [^b]* → matches all files not starting with b | Matches any one character not in the specified set. |

| [[:alpha:]] | ls [[:alpha:]]* → matches able, charlie ls *[[:alpha:]] → matches filea, testB | Matches alphabetic characters only (A–Z, a–z). |

| [[:lower:]] | ls [[:lower:]]* → matches able, baker ls *[[:lower:]] → matches filea, datax | Matches lowercase letters only. |

| [[:upper:]] | ls [[:upper:]]* → matches File1, Test ls *[[:upper:]] → matches fileA, dataX | Matches uppercase letters only. |

| [[:alnum:]] | ls [[:alnum:]]* → matches file1, test ls *[[:alnum:]] → matches data1, x9 | Matches letters and digits (A–Z, a–z, 0–9). |

| [[:punct:]] | ls [[:punct:]]* → matches _file, -data ls *[[:punct:]]* → matches data-file, name_test | Matches punctuation or symbols, not spaces or alphanumeric characters. |

| [[:digit:]] | ls [[:digit:]]* → matches 1file, 2025.txt ls *[[:digit:]] → matches file1, log9 | Matches digits only (0–9). |

| [[:space:]] | ls *[[:space:]]* → matches “my file.txt”, “test data.csv” ls *[[:space:]] → matches “data file” | Matches whitespace characters (space, tab, newline, etc.). |

Tilde Expansion (~)

- The tilde (

~) represents the home directory of the current or specified user. - Example:

[user@host home]$ ls ~root /root[user@host home]$ echo ~/home /home/user/home

Brace Expansion ({})

Used to generate multiple strings in one command. Braces contain:

A comma-separated list of strings, or

A sequence expression using

...

- Example:

[user@host home]$ echo {Sunday,Monday,Tuesday,Wednesday}.log Sunday.log Monday.log Tuesday.log Wednesday.log[user@host home]$ echo file{1..3}.txt file1.txt file2.txt file3.txt[user@host home]$ echo file{a..c}.txt filea.txt fileb.txt filec.txt[user@host home]$ echo file{a,b}{1,2}.txt filea1.txt filea2.txt fileb1.txt fileb2.txt[user@host home]$ echo file{a{1,2},b,c}.txt filea1.txt filea2.txt fileb.txt filec.txt

Note: You can replace echo with other commands like mkdir, touch, cat, less, etc., to perform actions on multiple files or directories at once.

Variable Expansion ($VARIABLE)

- Variables store values that can be expanded (substituted) in commands.

- Syntax:

VARIABLENAME=value echo $VARIABLENAME

- Example:

[user@host ~]$ USERNAME=operator [user@host ~]$ echo $USERNAME operator[user@host ~]$ echo ${USERNAME} operator

Command Substitution ($(command))

Replaces a command with its output.

- Example:

[user@host glob]$ echo The time is $(date +%M) minutes past $(date +%l%p). The time is 26 minutes past 11AM.

Protecting Arguments from Expansion

- To prevent unwanted shell expansions, you can use escaping or quoting.

- Escaping: Use

\(backslash) to protect the next character from expansion - Example:

[user@host glob]$ echo The value of \$HOME is your home directory. The value of $HOME is your home directory.

- Quoting: Controls how the shell interprets special characters.

- Single Quotes

' '→ Prevents all expansions. - Double Quotes

" "→ Prevents most expansions, but allows variable and command substitution.

- Single Quotes

- Example:

[user@host glob]$ myhost=$(hostname -s); echo $myhost host[user@host glob]$ echo "***** hostname is ${myhost} *****" ***** hostname is host *****[user@host glob]$ echo "Will variable $myhost evaluate to $(hostname -s)?" Will variable host evaluate to host?[user@host glob]$ echo 'Will variable $myhost evaluate to $(hostname -s)?' Will variable $myhost evaluate to $(hostname -s)?

Redirecting Output to a File or Program

You can send a command’s output to a file or another program instead of the terminal using redirection (>, >>) and pipelines (|). This helps save results or pass data seamlessly between commands.

Standard Input, Standard Output, and Standard Error

Every running program (process) interacts with three standard data streams called file descriptors:

| File Descriptor | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Standard Input (stdin) | Reads input (usually from the keyboard). |

| 1 | Standard Output (stdout) | Sends normal output to the terminal. |

| 2 | Standard Error (stderr) | Sends error messages to the terminal. |

Redirection allows these streams to be sent to or read from files instead.

Redirecting Output to a File

I/O redirection changes how a process reads or writes data. Instead of showing output on the terminal, it can be saved to a file or discarded.

If the file doesn’t exist → it’s created.

If the file exists → it’s overwritten unless using

>>(append).To discard unwanted data, redirect it to

/dev/null.

| Operator / Command | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

> | Redirects stdout (normal output) to a file, overwriting any existing content. | ls > files.txt |

>> | Redirects stdout and appends output to a file (does not overwrite). | echo "done" >> log.txt |

2> | Redirects stderr (error messages) to a file, overwriting existing content. | ls /root 2> errors.log |

2>> | Redirects stderr and appends to a file. | ls /root 2>> errors.log |

2> /dev/null | Discards error messages completely. | ls /root 2> /dev/null |

> file 2>&1 | Redirects both stdout and stderr to the same file (overwrite mode). | ls /root > all.log 2>&1 |

>> file 2>&1 | Redirects both stdout and stderr to the same file (append mode). | ls /root >> all.log 2>&1 |

&> file | Bash shortcut: redirects both stdout and stderr (overwrite mode). | ls &> output.log |

&>> file | Bash shortcut: redirects both stdout and stderr (append mode). | ls &>> output.log |

< file | Redirects stdin (input) from a file. | sort < names.txt |

Constructing Pipelines

A pipeline is a sequence of one or more commands separated by the pipe symbol (|).

It connects the stdout of one command to the stdin of the next.

Itsend output from one process directly into another.

Example:

ls -t | head -n 10 > /tmp/ten-last-changed-files→ List the 10 most recently modified files and save to a file.

tee combine redirection with a pipeline, it copies its stdin to both stdout and one or more files

Example:

ls -t | head -n 10 | tee /tmp/ten-last-changed-files→ Save final pipeline output and also show it on screen.

💡 Pro Tip: The order matters when redirecting both output and errors. the correct order is first stdout and then stderr.

Editing Text Files

Vim is one of the most powerful and widely used text editors in Linux and UNIX systems. It’s fast, efficient, and ideal for editing configuration files directly from the terminal even on remote servers. Knowing Vim ensures you can manage files without a graphical interface, making it an essential skill for every Linux user.

Vim can be accessed in two ways:

vi filename→ Lightweight version available with thevicommand (core editing features only)vim filename→ Full version with advanced features, syntax highlighting, and help system.

Basic Vim Workflow

- Open a file:

vim filename

-

Press

ito enter insert mode and start editing -

Press

Escto return to command mode -

Save your changes with

:wor save and quit with:wq -

Exit without saving using

:q! - Display absolute line numbers

:set number -

Undo the last change with

u -

Delete a single character with

x

Changing the Shell Environment

You can customize your shell environment by setting shell variables and environment variables. These variables can store values, simplify commands, and modify the behavior of the shell or programs run from it.

Shell Variables

-

Shell variables are local to a particular shell session.

-

Assign values using:

VARIABLENAME=value

- Example:

COUNT=40first_name=John

- Accessing variable values:

echo $COUNTecho ${COUNT}x

Environment Variables

- Environment variables are exported from the shell so programs can access them.

-

Export a variable:

export EDITOR=vim

-

Common environment variables:

-

PATH→ directories searched for executable programs -

HOME→ user’s home directory -

LANG→ locale and language settings

-

- Example:

export PATH=${PATH}:/home/user/sbinexport LANG=fr_FR.UTF-8

Automatic Variable Setup

-

To set variables automatically at shell startup, edit Bash startup scripts like

~/.bashrc:vim ~/.bashrcPATH="$HOME/.local/bin:$HOME/bin:$PATH" export PATH export EDITOR=vim

Unsetting and Unexporting Variables

-

Remove a variable entirely:

unset PS1

-

Remove export without unsetting:

export -n PS1

Managing Users and Groups

Users

A user represents an account on the system that can log in and access resources.

Each user has a unique username and a user ID (UID).

Users can have different levels of privileges:

Root user (

UID 0) → Superuser with full system control (UID 0).Regular users → Created for normal activities, with limited access.

- System User → Used for system processes and services (non-login accounts).

- You can use the

idcommand to show information about the currently logged-in user, also you can pass the username to theidcommand as an argument to information about another user - Example:

[user01@host ~]$ id uid=1000(user01) gid=1000(user01) groups=1000(user01) context=unconfined_u:unconfined_r:unconfined_t:s0-s0:c0.c1023[user01@host]$ id user02 uid=1002(user02) gid=1001(user02) groups=1001(user02) context=unconfined_u:unconfined_r:unconfined_t:s0-s0:c0.c1023

- All user account information are stored in /etc/passwd file, where each line represents one user, with fields separated by colons (

:)username:password:UID:GID:GECOS:home_directory:shell→ Syntax of /etc/passwdalice:x:1001:1001:Alice Smith:/home/alice:/bin/bash→ entry in /etc/passwd

getent passwd username→ Displays user info from /etc/passwd.

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

username | Login name |

x | Placeholder for password (actual passwords are stored in /etc/shadow) |

UID | User ID number |

GID | Primary group ID number |

GECOS | User information (full name, contact, etc.) |

home_directory | Path to the user’s home folder |

shell | Default shell for the user (e.g., /bin/bash) |

Groups

A group is a collection of users. Groups are used to manage permissions collectively.

Each group has a group name and a group ID (GID).

A user can belong to one primary group and multiple secondary groups.

implifies file permission management.

Allows multiple users to share access to files and directories without giving them full system access.

groups alice→ Lists all groups user ‘alice’ belongs to- All group information are stored in /etc/group

file, where each line represents one group, with fields separated by colons (:)group_name:password:GID:user_list→ Syntax of /etc/groupdevteam:x:1002:alice,bob,charlie→ entry in /etc/group

getent group groupname→ Displays group info from /etc/group.

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

group_name | Name of the group |

x | Placeholder for group password (rarely used) |

GID | Group ID number |

user_list | Comma-separated list of users in this group |

Superuser Access

The Superuser (Root) user has complete control over a Linux system including files, users, and devices.

Normal users have limited access; for example, they can manage USB devices but cannot modify system files.

The root account is equivalent to the Administrator account in Windows.

For security reasons, it’s recommended not to log in directly as root. Instead, log in as a normal user and use commands like

suorsudowhen administrative privileges are needed.

- Two common ways to start a root shell:

sudo -i→ Starts an interactive root shell with login scripts.sudo su -→ Starts a full root login shell.

- Both achieve similar results, but

sudo -iis generally preferred in Red Hat systems.

Switching Users

The

su(substitute user) command allows switching to another user account.su - username→ Syntax- Example:

[user1@host ~]$ su - user2 Password: [user2@host ~]$su -→ switches to root

Running Commands with sudo

The

sudocommand allows a permitted user to run commands as another user (usually root).Unlike

su, it asks for the user’s own password, not the root password.Example:

[user01@host ~]$ sudo usermod -L user02 [sudo] password for user01:

- Every sudo action is recorded in

/var/log/secure.

Configuring Sudo Access

The

sudocommand allows users to run commands with the privileges of another user, typically the root user. Proper configuration ensures secure and controlled administrative access.The main configuration file for sudo is /etc/sudoers. Always edit with

visudoto prevent syntax errors.%wheel ALL=(ALL) ALL%wheel→ applies to the wheel group.ALL=(ALL)→ can run commands as any user on any host.Final

ALL→ can run any command.

Files in

/etc/sudoers.d/are automatically included by/etc/sudoers. The permission for those files should be 440- To grants sudo to a specific user, you would create a file

/etc/sudoers.d/user01with the following content:user01 ALL=(ALL) ALL

- To grants sudo to a group, you would create a file

/etc/sudoers.d/group01with the following content:%group01 ALL=(ALL) ALL

ansible ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD:ALL→ To allow a user to run commands without a password (commonly used in automation or cloud setups)

Managing Users

- The useradd and usermod commands in Linux are used to create and manage user accounts.

- They allow administrators to define user details such as home directories, shells, group memberships, and account permissions efficiently.

- When a user is added, a home directory is usually created, a primary group with the same name is assigned, and any additional groups the user belongs to are called supplementary groups.

| Command | Option | Description |

|---|---|---|

| useradd, usermod | -c "comment" | Add or update the user’s description or comment field (real name, etc.). |

| useradd, usermod | -d /path/to/home | Specify a custom home directory for the user account. |

| useradd, usermod | -m | Create the home directory if it doesn’t exist (useradd) or move it to a new locationwith usermod -d. |

| useradd, usermod | -s /bin/bash | Set or change the user’s login shell. |

| useradd | -u UID | Assign a specific User ID number. |

| useradd, usermod | -g group | Assign a primary group for the user account. |

| useradd, usermod | -G group1,group2 | Add or set additional (supplementary) groups for the user. |

| usermod | -a | Append the user to supplementary groups instead of replacing existing ones (used with-G). |

| useradd | -e YYYY-MM-DD | Set an account expiration date. |

| useradd | -p password | Assign an encrypted password for the user account. |

| usermod | -L | Lock the user account (disables login). |

| usermod | -U | Unlock a previously locked user account. |

- Example:

useradd user01useradd -m -c "Dev User" -s /bin/bash -G devteam johnusermod -aG docker john→ -aG command adds user to a supplementary groupusermod -g group01 user02→ -g option here with usermod command create a different primary group for the user

- The passwd command is used to set the password for the user, Only root can change other users’ passwords.

- Example:

passwd user01→ This will prompt the user to enter the password for user01

- The userdel command is used to delete a user account from the system. It should be used with the

-roption to ensure that the user’s home directory and mail spool are also removed. - Example:

userdel user01→ Deletes the user, but the home directory remains.userdel -r john→ Deletes the user and their home directory.

- Red Hat Enterprise Linux uses specific UID numbers and ranges for different purposes:

UID 0 → Always assigned to the superuser account (

root).UID 1–200 → “System users” assigned statically to system processes by Red Hat.

UID 201–999 → “System users” used by processes that do not own files; typically assigned dynamically when software is installed. These unprivileged users have limited access to system resources.

UID 1000+ → Available for assignment to regular users.

Managing Groups

- A group must exist before a user can be added to that group.

- Groups help manage permissions and access control for multiple users efficiently.

- The groupadd command is used to create new group in the system.

| Command | Option | Description |

|---|---|---|

groupadd | -g GID | Assign a specific Group ID. |

groupadd | -r | Create a system group (typically with a GID < 1000). |

- Example:

groupadd developersgroupadd -g 1050 adminsgroupadd -r group02

- The groupmod is used to change the group details, such as name of GID

| Command | Option | Description |

|---|---|---|

groupmod | -g GID | Change the group ID. |

groupmod | -n new_name old_name | Rename the group. |

- Example:

groupmod -g 1200 developersgroupmod -n devteam developers

- The groupdel command is used to remove the group from the system.

- A group cannot be deleted if it is the primary group of any existing user.

- You must modify or delete the user first before removing the group.

- Example:

groupdel devteam

Managing User Passwords

- User password management in Linux is critical for security and access control. Passwords, aging policies, and account restrictions are managed through files like

/etc/shadowand commands such aspasswd,chage, andusermod. - The passwords stored in

/etc/shadoware encrypted and accessible only by root. - Example: Entry of

/etc/shadowfileuser01:$6$CSsXcYG1L/4ZfHr/$2W6evvJahUfzfHpc9X.45Jc6H30E...:19500:0:90:7:14:20000:

- Each line in

/etc/shadowcontains nine colon-separated fields, including:

| Field Name | Example Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

Username | user01 | The account name. |

Encrypted Password | $6$CSsXcYG1L/4ZfHr/$2W6evvJahUfzfHpc9X.45Jc6H30E... | Hashed password using SHA-512. |

Last Password Change | 19500 | Days since 1970-01-01 when the password was last changed. |

Minimum Days | 0 | Minimum number of days before the password can be changed again. |

Maximum Days | 90 | Maximum number of days before the password must be changed. |

Warning Period | 7 | Number of days before expiration that the user is warned. |

Inactivity Period | 14 | Days after password expiry before the account is disabled. |

Account Expiration Date | 20000 | Date (in days since 1970-01-01) when the account will expire. |

Reserved Field | (empty) | Reserved for future use; usually left blank. |

An encrypted password entry looks like:

$6$CSsXcYG1L/4ZfHr/$2W6evvJahUfzfHpc9X.45Jc6H30E...$6$→ SHA-512 algorithmCSsXcYG1L/4ZfHr/→ Salt (random data to strengthen security)Remainder → Encrypted password hash

You can manage password aging with the

chagecommand:

| Command Example | Description |

|---|---|

sudo chage -m 0 -M 90 -W 7 -I 14 user01 | Set minimum (0), maximum (90), warning (7), and inactivity (14) days. |

sudo chage -d 0 user01 | Force user to change password at next login. |

sudo chage -E 2025-12-31 user01 | Expire account on a specific date. |

sudo chage -l user01 | Display password aging information. |

- Default password aging rules are set in

/etc/login.defsusing:PASS_MAX_DAYS→ Max password agePASS_MIN_DAYS→ Min password agePASS_WARN_AGE→ Warning period before expiration

- Restricting account access (locking) is preferred over deletion when temporarily disabling a user, such as during employee offboarding.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

sudo usermod -L username | Lock user account (disable password login). |

sudo usermod -U username | Unlock user account. |

sudo usermod -L -e 2025-12-31 username | Lock and expire the account simultaneously. |

- For accounts that should not log in interactively (like service accounts), assign the

nologinshell:sudo usermod -s /sbin/nologin username

- This enhances security while still allowing background processes (like mail or services) to use the account.

Controlling Access to Files

Linux permissions determine what users can do with files and directories. Permissions are divided into three types: read (r), write (w), and execute (x), and apply to owner, group, and others.

| Permission | Effect on Files | Effect on Directories |

|---|---|---|

| r | Can read the file contents | Can list file names in the directory |

| w | Can modify the file contents | Can create or delete files in the directory |

| x | Can execute the file as a command | Can access directory contents and traverse it if file permissions allow |

The ls -l command shows detailed information about files and directories:

-

[user@host ~]$ ls -l test -rw-rw-r-- 1 student student 0 Feb 8 17:36 test -

[user@host ~]$ ls -ld /home drwxr-xr-x 5 root root 4096 Jan 31 22:00 /home

Below is a breakdown of the ls -l command output to help you understand what each part represents.

- First character: File type

-

-→ Regular file -

d→ Directory -

l→ Symbolic link -

b/c→ Block/character device -

p/s→ Special-purpose files

-

- Next nine characters: Permissions

-

1st set of 3 characters → Owner

-

2nd set of 3 characters→ Group

-

3rd set of 3 characters→ Others

-

r= read,w= write,x= execute -

-= permission not granted

-

- Number: Number of hard links

- Owner and group: File ownership

- Example:

-

-rw-rw-r-- 1 student student-

Owner → read & write

-

Group → read & write

-

Others → read only

-

-

drwxr-xr-x 5 root root-

Owner → read, write, execute

-

Group → read & execute

-

Others → read & execute

-

-

ls -l output (_ in _rwxrwxrwx), can vary depending on file type or special flags.

Numeric Permissions

- Each permission has a numeric value:

-

r = 4→ Readw = 2→ Writex = 1→ Execute

- Numeric permission calculation:

-

- Example:

rwx→ 4 + 2 + 1 = 7 - Example:

rw-→ 4 + 2 + 0 = 6 - Example:

r--→ 4 + 0 + 0 = 4 - Example:

r-x→ 4 + 0 + 1 = 5

- Example:

File Permissions and Ownership

The chmod command is used to change file and directory permissions. It stands for “change mode”, since permissions are also known as the mode of a file.

The command accepts a permission instruction followed by one or more files or directories.

Permissions can be changed in two ways:

-

Symbolic method

-

Numeric (octal) method

Symbolic Method

chmod [Who][What][Which] file|directory| Part | Meaning | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Who | Whose permissions to change | u = user (owner), g = group, o = others, a = all |

| What | Action to perform | + = add, - = remove, = = set exactly |

| Which | Which permissions | r = read, w = write, x = execute |

You can modify one or more existing permissions without resetting all of them.

Use:

-

+to add -

-to remove -

=to set exact permissions

chmod go-rw file1→ Remove read and write permission for group and others onfile1chmod a+x file2→ Add execute permission for everyone onfile2

Using an uppercase X instead of lowercase x adds execute permission only if the file is a directory or already executable for user, group, or others.

The -R option applies changes recursively to all files and subdirectories.

Example:

-

chmod -R g+rwX demodir -

Adds read and write permissions for the group on

demodirand all its contents. -

Adds execute permission only to directories or files that already have execute permission.

Numeric(Octal) Method

chmod ### file|directoryEach digit represents permissions for user, group, and others, in that order.

| Level | Permissions | Calculation | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| User | rwx |

4+2+1 |

7 |

| Group | r-x |

4+0+1 |

5 |

| Others | --- |

0+0+0 |

0 |

Numeric code: 750

chmod 750 filenameExample:

chmod 644 samplefile→ User: read/write, Group: read, Others: readchmod 750 sampledir→ User: read/write/execute, Group: read/execute, Others: none

Changing File and Directory Ownership

When a file is created, it is owned by:

-

The user who created it.

-

The user’s primary group (usually a private group for that user).

Sometimes, ownership must be changed to grant access to another user or group.

The chown command is used to changed the ownership of files and directories

chown [OPTION] OWNER:GROUP FILE|DIRECTORY-

Only root can change file ownership.

-

Both root and file owner can change group ownership (if the owner is a member of that group).

- We can mention just the Owner or Group or Both

chown student test_file→ Changes owner oftest_fileto userstudentchown -R student test_dir→ Recursively changes ownership oftest_dirand its contents tostudentchown :admins test_dir→ Changes the group oftest_dirtoadminschown visitor:guests test_dir→ Changes both owner tovisitorand group toguests

Alternatively, group ownership can be changed using chgrp command

-

chgrp groupname file|directory -

chgrp admins test_dir

Special Permissions in Linux

Special permissions are advanced access features that extend beyond basic user, group, and other permissions. They modify how files and directories behave when accessed or executed.

| Special Permission | Effect on Files | Effect on Directories |

|---|---|---|

| u+s (setuid) | File executes as the file owner, not the user running it. | No effect. |

| g+s (setgid) | File executes as the file’s group, not the user’s group. | Files created inside inherit the directory’s group ownership. |

| o+t (sticky bit) | No effect. | Users can only delete their own files even if they have write access to the directory. |

ls -l command and examining the output.

Refer to the table below for examples of how special permission bits appear in listings.

| Example | Meaning |

|---|---|

-rwsr-xr-x → s replaces x in owner field |

setuid active (e.g., /usr/bin/passwd) |

drwxr-sr-x → s replaces x in group field |

setgid active (e.g., /run/log/journal) |

drwxrwxrwt → t replaces x in others field |

sticky bit active (e.g., /tmp) |

- Symbolic

u+s,g+s,o+t→ Syntax-

chmod g+s directory→ Example

- Numeric (4th digit)

4= setuid,2= setgid,1= sticky → Syntaxchmod 2770 directory→ Example

Default Permissions & umask

When a file or directory is created, it’s assigned default permissions determined by two factors:

-

Type of item (file or directory)

-

User’s umask (user file-creation mode mask)

The default permission before applying umask for file is 0666 (-rw-rw-rw-) and for directory is 0777 (drwxrwxrwx)

umask defines which permission bits should be removed (masked) from the default permission set when new files or directories are created.

Example:

[user@host ~]$ umask 0002-

This clears the write bit for others, resulting in:

-

New file →

-rw-rw-r-- -

New directory →

drwxrwxr-x

-

| umask | File Permissions | Directory Permissions | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

0002 |

-rw-rw-r-- |

drwxrwxr-x |

Default for collaborative environments |

0000 |

-rw-rw-rw- |

drwxrwxrwx |

Everyone has full access |

007 |

-rw-rw---- |

drwxrwx--- |

Restricts access to others |

027 |

-rw-r----- |

drwxr-x--- |

Secure default; no access for others |

umask 027, where 027 represents the permission mask value and can be changed to any valid octal value as needed.

To make the umask configuration persistent, modify the global settings in /etc/profile or /etc/bashrc. For user-specific overrides, make changes in the ~/.bashrc or ~/.bash_profile files.

You must log out and back in for global umask changes to take effect. Access Control List (ACL)

Standard Linux file permissions work well when files are used by a single owner and one group.

However, when files must be accessed by multiple users or groups with different permission sets, Access Control Lists (ACLs) come into play.

ACLs allow administrators to grant permissions to multiple named users or groups (by username, group name, UID, or GID) using the same permission flags as standard file permissions:

- r – read

- w – write

- x – execute

Named users and groups are not visible in a simple ls -l output, they are stored within the ACL structure.

Who Can Set ACLs

File owners can set ACLs on their own files or directories.

Privileged users with the

CAP_FOWNERcapability can set ACLs on any file or directory.Inheritance: New files and subdirectories inherit ACLs from their parent directory’s default ACL, if one exists.

Note: The parent directory must have the execute (search) permission set for named users/groups to access the contents.

File-System ACL Support

File systems must have ACL support enabled.

XFS: ACLs are built-in.

ext3/ext4 (RHEL 8 and later): ACL option enabled by default.

Older systems: Verify ACL support manually.

You can enable ACL support by mounting the filesystem with the acl option:

mount -o acl /dev/sdX /mountpoint

Or, persist it in /etc/fstab:

UUID=<id> /data ext4 defaults,acl 0 2

Viewing and Interpreting ACL Permissions

The ls -l command gives a minimal hint of ACLs:

[user@host content]$ ls -l reports.txt -rwxrw----+ 1 user operators 130 Mar 19 23:56 reports.txt

The + at the end of the permission string means extended ACLs exist.

| Field | Meaning |

|---|---|

| user: | User ACL (same as file owner permissions) |

| group: | Current ACL mask, not group owner permissions |

| other: | Same as standard “other” file permissions |

Viewing File ACLs

Use getfacl to display ACLs:

[user@host content]$ getfacl reports.txt # file: reports.txt # owner: user # group: operators user::rwx user:consultant3:--- user:1005:rwx #effective:rw- group::rwx #effective:rw- group:consultant1:r-- group:2210:rwx #effective:rw- mask::rw- other::---

Breakdown:

- Commented Entries

# file: File name

# owner: File owner

# group: Group owner

- User Entries

user::rwx→ File owner permissionsuser:consultant3:---→ Named user (no permissions)user:1005:rwx #effective:rw-→ Named user limited by mask

- Group Entries

group::rwx #effective:rw-→ Group owner limited by maskgroup:consultant1:r--→ Named group (read-only)group:2210:rwx #effective:rw-→ Named group limited by mask

- Mask Entry

mask::rw-→ Maximum allowed permissions for named users/groups

- Other Entry

other::---→ No permissions for anyone else

Viewing Directory ACLs

Use getfacl to display ACLs:

[user@host content]$ getfacl . # file: . # owner: user # group: operators # flags: -s- user::rwx user:consultant3:--- group::rwx group:consultant1:r-x mask::rwx other::--- default:user::rwx default:group::rwx default:mask::rwx default:other::---

The execute (x) permission allows directory traversal/search.

Default ACLs determine permissions for newly created files or subdirectories.

Breakdown:

default:user::rwx→ Default owner permissionsdefault:user:name:rx→ Default named user permissionsdefault:group::rwx→ Default group permissionsdefault:mask::rwx→ Maximum default permissionsdefault:other::---→ No permissions for others

Default ACLs do not grant access to the directory itself, they define inheritance rules for new files/subdirectories.

ACL Mask

The ACL mask defines the maximum permissions possible for:

Named users

The group owner

Named groups

It does not affect the file owner or “others”.

View mask:

getfacl fileSet mask:

setfacl -m m::perms file

When ACLs change, the mask is recalculated automatically unless you use the -n flag or explicitly redefine it.

ACL Permission Precedence

When a process accesses a file:

If user = owner → use file owner ACL

If user matches named user entry → use that entry (limited by mask)

If group matches group owner or named group → use that group’s ACL (limited by mask)

Else → apply the

otherACL

Changing ACL Permissions

The setfacl command is used to add, modify, or remove ACLs.

| Command | Purpose |

|---|---|

setfacl -m u:name:rX file | Add or modify a user ACL |

setfacl -m g:name:rw file | Add or modify a group ACL |

setfacl -m o::- file | Modify other permissions |

setfacl -m u::rwx,g:consultants:rX,o::- file | Combine multiple entries in one command |

getfacl file-A | setfacl --set-file=- file-B | Use getfacl output as input to copy ACLs between files |

setfacl -m m::r file | Set explicit ACL mask (restrict named users and groups to read-only) |

setfacl -R -m u:name:rX directory | Apply ACL recursively; uppercase X sets execute only on directories |

setfacl -x u:name,g:name file | Remove specific ACL entries |

setfacl -b file | Remove all ACLs from a file |

setfacl -m d:u:name:rx directory | Set default ACLs on directories (files inherit permissions; directories get execute if x included) |

setfacl -x d:u:name directory | Delete a specific default ACL entry |

setfacl -k directory | Delete all default ACLs on a directory |

getfacl file | View ACLs |

setfacl -m | Modify/add ACLs |

setfacl -x | Delete specific ACL entries |

setfacl -b | Remove all ACLs |

setfacl -k | Remove all default ACLs |

setfacl -R | Apply changes recursively |

mount -o acl | Enable ACL support on mount |

Monitoring and Managing Linux Processes

Linux Process

A process is a running instance of a program. When you launch an executable, Linux creates a process for it.

A process includes:

Allocated memory space

Security details (user, group, privileges)

One or more execution threads

A unique Process ID (PID)

Every process is started by another process, called its parent, identified by the Parent Process ID (PPID).

The first process on a Linux system is systemd, and all others are its descendants.

When a new process is created, the parent duplicates itself using fork(), and the new child may replace its program using exec().

After finishing, the child exits, and the parent removes its record from the process table.

Process States

In a multitasking OS, each CPU runs only one process at a time.

Linux assigns every process a state based on what it’s doing.

| State | Flag | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Running | R | The process is currently running or ready to run. |

| Sleeping | S | Waiting for an event, resource, or signal. |

| Uninterruptible Sleep | D | Waiting for hardware or I/O; cannot be interrupted. |

| Stopped | T | Suspended (for debugging or via signal like Ctrl+Z). |

| Zombie | Z | Process finished but not yet removed from the process table. |

You can view process states in the S column of top or the STAT column of ps

Viewing Processes in Linux

The ps command (Process Status) displays details about currently running processes which includes user, PID, parent process, CPU/memory usage, state, and command name.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

ps aux | BSD-style full listing (shows all users and processes). |

ps -ef | UNIX/POSIX-style full listing of all processes. |

ps --forest | Displays processes in a tree view (parent → child relationships). |

ps -eo pid,user,%cpu,%mem,cmd | Shows custom columns (script-friendly). |

--sort | Sorts output (e.g., --sort=-%mem for top memory consumers). |

pstree | Displays all running processes in a tree-like hierarchical structure. |

top | Displays real-time, dynamic process information including CPU and memory usage. |

Example:

$ ps -ef UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD root 1 0 0 17:45 ? 0:03 /usr/lib/systemd/systemd root 2 0 0 17:45 ? 0:00 [kthreadd] root 2149 1 0 18:07 pts/0 0:00 bash user 2205 2149 0 18:08 pts/0 0:00 ps -ef- UNIX/POSIX-style with UID, PID, PPID, STIME, CMD columns.

$ ps aux USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND root 1 0.0 0.1 51648 7504 ? Ss 17:45 0:03 /usr/lib/systemd/systemd root 2 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S 17:45 0:00 [kthreadd] student 2149 0.0 0.2 266904 3836 pts/0 R+ 18:07 0:00 ps aux- BSD-style format with

%CPU,%MEM, VSZ/RSS columns.

- BSD-style format with

$ ps --forest PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND 2149 pts/0 Ss 0:00 bash 2205 pts/0 R+ 0:00 \_ ps --forestShows hierarchical (parent → child) relationships.

$ pstree systemd─┬─NetworkManager ├─sshd───bash───ps └─cronDisplays process hierarchy as a tree.

$ ps -eo pid,user,%mem,cmd --sort=-%mem | head -n 10Shows the top 10 memory-consuming processes.

Jobs and Sessions

Job control is a feature of the shell that allows a single shell instance to run and manage multiple commands.

What is a Job?

A job is associated with each pipeline entered at a shell prompt.

All processes in that pipeline belong to the same process group.

A single command is treated as a minimal pipeline, creating a job with only one member.

Foreground vs Background Processes

Only one job can read input and keyboard-generated signals from a terminal at a time.

Processes in this job are foreground processes of that terminal.

Background processes:

Cannot read input from the terminal.

May still write output to the terminal.

Can be running or stopped (suspended).

A background process attempting to read input will automatically be suspended.

Sessions

Each terminal is its own session with:

A foreground process.

Any number of background processes.

A job belongs to exactly one session (its controlling terminal).

Processes started by the system (e.g., daemons) have no controlling terminal. In

ps, they show?in the TTY column.

Running Jobs in the Background

Append an ampersand

&to run a command or pipeline in the background:[user@host ~]$ sleep 10000 &[1] 5947 [user@host ~]$

Listing Jobs

- Use the

jobscommand to see jobs being tracked by Bash: [user@host ~]$ jobs [1]+ Running sleep 10000 [user@host ~]$

Foreground a background job

[user@host ~]$ fg %1 sleep 10000

Suspend a foreground process

- Press

Ctrl+Z sleep 10000 ^Z [1]+ Stopped sleep 10000- The shell warns users who try to exit a terminal with suspended jobs. Exiting again kills suspended jobs.

Resume suspended process in background

[user@host ~]$ bg %1 [1]+ sleep 10000 &

Viewing Jobs

ps jcommand shows process, job, and session info[user@host ~]$ ps j PPID PID PGID SID TTY TPGID STAT UID TIME COMMAND 2764 2768 2768 2768 pts/0 6377 Ss 1000 0:00 /bin/bash 2768 5947 5947 2768 pts/0 6377 T 1000 0:00 sleep 10000 2768 6377 6377 2768 pts/0 6377 R+ 1000 0:00 ps j

| Field | Meaning |

|---|---|

| PID | Process ID |

| PPID | Parent Process ID |

| PGID | Process Group ID (job leader) |

| SID | Session ID (usually the interactive shell) |

| STAT | Process state (e.g., T = stopped) |

Killing Processes

A signal is a software interrupt delivered to a process, reporting events such as errors, external events (I/O requests, expired timers), or explicit commands/keyboard sequences.

| Signal No | Short Name | Definition / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | HUP | Hangup; report termination of the controlling process of a terminal or request process reinitialization (e.g., config reload). |

| 2 | INT | Keyboard interrupt; causes program termination. Sent via Ctrl+C. |

| 3 | QUIT | Keyboard quit; similar to SIGINT but generates a core dump. Sent via Ctrl+\. |

| 9 | KILL | Unblockable; causes abrupt program termination. Cannot be blocked, ignored, or handled. |

| 15 | TERM | Default terminate; polite way to ask a program to exit. Can be blocked or handled by the process. |

| 18 | CONT | Continue; resume a stopped process. Cannot be blocked. |

| 19 | STOP | Stop; unblockable suspend of a process. |

| 20 | TSTP | Keyboard stop; similar to STOP but can be blocked or handled. Sent via Ctrl+Z. |

Default Signal Actions

Term – terminate process immediately.

Core – terminate process and save memory image (core dump).

Stop – suspend process, wait to continue (resume).

Sending Signals to Processes using Keyboard

Ctrl+C – SIGINT

Ctrl+Z – SIGTSTP (suspend)

Ctrl+\ – SIGQUIT (core dump)

Sending Signals to Processes using Commands

kill – send a signal to a process by PID.

[user@host ~]$ kill -l 1) SIGHUP 2) SIGINT 3) SIGQUIT 4) SIGILL 5) SIGTRAP 6) SIGABRT 7) SIGBUS 8) SIGFPE 9) SIGKILL 10) SIGUSR1 11) SIGSEGV 12) SIGUSR2 13) SIGPIPE 14) SIGALRM 15) SIGTERM 16) SIGSTKFLT 17) SIGCHLD 18) SIGCONT 19) SIGSTOP 20) SIGTSTP

Example

[user@host ~]$ ps aux | grep job 5194 0.0 0.1 222448 2980 pts/1 S 16:39 0:00 /bin/bash control job1 5199 0.0 0.1 222448 3132 pts/1 S 16:39 0:00 /bin/bash control job2 5205 0.0 0.1 222448 3124 pts/1 S 16:39 0:00 /bin/bash control job3 [user@host ~]$ kill 5194 [1] Terminated control job1 [user@host ~]$ kill -9 5199 [2]- Killed control job2 [user@host ~]$ kill -SIGTERM 5205 [3]+ Terminated control job3

killall – signal multiple processes by command name.

killall control→ This is an example command, here control is the command name

pkill – signal processes based on command name, UID, GID, terminal, parent PID, etc.

[user@host ~]$ pkill control [1] Terminated control pkill1 [2]- Terminated control pkill2 [3]+ Terminated control pkill3

Logging Users Out Administratively

Identify login sessions with

w:[user@host ~]$ w USER TTY FROM LOGIN@ IDLE JCPU PCPU WHAT root tty2 12:26 14:58 0.04s 0.04s -bash bob tty3 12:28 14:42 0.02s 0.02s -bash user pts/1 desk.example.com 12:41 2.00s 0.03s 0.03s w

Terminate processes by user:

[root@host ~]# pgrep -l -u bob 6964 bash 6998 sleep 6999 sleep [root@host ~]# pkill -SIGKILL -u bob [root@host ~]# pgrep -l -u bob # No processes remain

Terminate processes by terminal:

[root@host ~]# pkill -t tty3 [root@host ~]# pkill -SIGKILL -t tty3

- Terminate child processes using parent PID:

[root@host ~]# pstree -p bob bash(8391)─┬─sleep(8425) ├─sleep(8426) └─sleep(8427) [root@host ~]# pkill -P 8391 # Kill all children of bash [root@host ~]# pkill -SIGKILL -P 8391

Monitoring Process Activity

Load average is a measurement provided by the Linux kernel that represents the perceived system load over time. It gives a rough gauge of how many system resource requests are pending and whether system load is increasing or decreasing.

Every five seconds, the kernel collects the current load number based on the number of processes in runnable (R) and uninterruptible (D) states.

This number is then reported as an exponential moving average over the most recent 1, 5, and 15 minutes.

Commands That Show Load Average

uptimewtop

Load Average Calculation

The load average represents how many processes are ready to run or waiting for I/O (disk/network).

The value includes:

Processes waiting for CPU (state R)

Processes waiting for I/O completion (state D)

If load averages are high while CPU activity is low, check for heavy disk or network activity.

You can view the current load average using the

uptimecommand:[user@host ~]$ uptime 15:29:03 up 14 min, 2 users, load average: 2.92, 4.48, 5.20

The three numbers represent the load over the last 1, 5, and 15 minutes.

Per-CPU Load

- If load mainly comes from CPU-bound processes, divide the load average by the number of logical CPUs to check whether the system is overloaded.

- Use

lscputo determine CPU count:[user@host ~]$ lscpu Architecture: x86_64 CPU op-mode(s): 32-bit, 64-bit Byte Order: Little Endian CPU(s): 4 On-line CPU(s) list: 0-3 Thread(s) per core: 2 Core(s) per socket: 2 Socket(s): 1 NUMA node(s): 1 ...output omitted...

- This is a 4 logical CPU system (2 cores × 2 threads).

- Now divide the load average by 4:

- Load average: 2.92, 4.48, 5.20

- Number of logical CPUs: 4

- Per-CPU load (Load average ÷ CPUs): 0.73, 1.12, 1.30

- Interpretation:

- – 0.73 (1 min): CPUs ~73% utilized, normal.

- – 1.12 (5 min): ~112% utilized, ~12%overloaded.

- – 1.30 (15 min): ~130% utilized, ~30%overloaded.

A load value of 0 = idle CPU queue (no waiting processes).

A load value of 1 = one process actively using a CPU (no wait).

Load increases as more processes wait for CPU or I/O.

- Processes waiting for I/O also increase the load average, even if CPU usage is low, since they represent blocked tasks.

- A load average below 1 (per CPU) means the system is performing efficiently.

- Once utilization approaches 100%, new processes must wait, and load numbers climb above 1.

Real-Time Process Monitoring

- The

topprogram provides a continuously updating view of active processes. - Unlike

ps,topupdates dynamically at a configurable interval.

| Column | Description |

|---|---|

| PID | Process ID |

| USER | Owner of the process |

| VIRT | Total virtual memory used (includes code, data, shared libs, and swapped pages), same as VSZ in ps |

| RES | Physical resident memory (same as RSS in ps) |

| S | Process state: • D = Uninterruptible sleep • R = Running • S = Sleeping • T = Stopped/Traced • Z = Zombie |

| TIME | Total CPU time used since process start |

| COMMAND | Process command name |

Fundamental Keystrokes in top

| Key | Purpose |

|---|---|

? or h | Help for interactive keystrokes |

l, t, m | Toggle load, threads, or memory header lines |

1 | Show individual CPU stats or a combined summary |

s | Change refresh rate (e.g., 0.5, 1, 5 seconds) |

b | Toggle reverse highlight for running processes |

Shift + b | Enable bold display for header and running processes |

Shift + h | Toggle between processes and threads view |

u, Shift + u | Filter by user name |

Shift + m | Sort by memory usage (descending) |

Shift + p | Sort by CPU usage (descending) |

k | Kill a process (prompt for PID and signal) (not available in secure mode) |

r | Renice a process (prompt for PID and nice value) (not available in secure mode) |

Shift + w | Save display configuration for next run |

q | Quit top |

f | Manage columns (enable/disable fields and change sort order) |

Process Scheduling

Different processes have different levels of importance.

Scheduling policies: Most processes run under

SCHED_OTHER(orSCHED_NORMAL).Nice value: Determines relative priority.

Nice level range:

-20→ highest priority0→ default19→ lowest priority

Rules:

Higher nice level → less CPU priority (process gives up CPU easily).

Lower nice level → higher CPU priority.

If there are fewer processes than CPUs, even high nice level processes get full CPU time.

Nice Levels

Only root may reduce a process nice level.

Unprivileged users can only increase the nice level of their own processes(max 19.

- Reporting Nice Levels Using

top- The NI column → process nice value

- The PR column → scheduled priority

- Example:

- Nice

-20→ PR0 - Nice

19→ PR39

- Nice

- Reporting Nice Levels Using

ps [user@host ~]$ ps axo pid,comm,nice,cls --sort=-nice PID COMMAND NI CLS 30 khugepaged 19 TS 29 ksmd 5 TS 1 systemd 0 TS 2 kthreadd 0 TS 9 ksoftirqd/0 0 TS 10 rcu_sched 0 TS 11 migration/0 - FF 12 watchdog/0 - FF

TS → SCHED_NORMAL

– → other scheduling policies

Starting Processes with Different Nice Levels

- Inherit nice level from shell

[user@host ~]$ sha1sum /dev/zero & [1] 3480 [user@host ~]$ ps -o pid,comm,nice 3480 PID COMMAND NI 3480 sha1sum 0

- Using

nicecommand (default 10)[user@host ~]$ nice sha1sum /dev/zero & [1] 3517 [user@host ~]$ ps -o pid,comm,nice 3517 PID COMMAND NI 3517 sha1sum 10

- Using

nice -nfor custom nice level[user@host ~]$ nice -n 15 sha1sum & [1] 3521 [user@host ~]$ ps -o pid,comm,nice 3521 PID COMMAND NI 3521 sha1sum 15

- Changing the Nice Level of an Existing Process Using

renice[user@host ~]$ renice -n 19 3521 3521 (process ID) old priority 15, new priority 19

Controlling Services and Daemons

Introduction To Systemd

systemd manages startup and services in Linux, including activation of system resources, daemons, and processes.

Daemons run in the background, usually starting automatically at boot.

Many daemon names end with ‘d’ (e.g.,

sshd,crond).A service in systemd may be a daemon or a one-time action (called oneshot).

| Unit Type | Extension | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Service | .service | Represents a system service or daemon managed by systemd. |

| Socket | .socket | Monitors an IPC socket and automatically starts the corresponding service when a connection request arrives. |

| Path | .path | Starts a service when a specific file or directory is created, modified, or deleted. |

- To view available unit types:

systemctl -t help

Listing Services

- List all loaded and active services

[root@host ~]# systemctl list-units --type=service UNIT LOAD ACTIVE SUB DESCRIPTION atd.service loaded active running Job spooling tools auditd.service loaded active running Security Auditing Service chronyd.service loaded active running NTP client/server crond.service loaded active running Command Scheduler dbus.service loaded active running D-Bus System Message Bus getty@tty1.service loaded active running Getty on tty1 NetworkManager.service loaded active running Network Manager systemd-journald.service loaded active running Journal Service systemd-logind.service loaded active running Login Service systemd-udevd.service loaded active running Rule-based Manager for Device Events and Files ...output truncated...

UNIT – Service unit name

LOAD – Whether systemd loaded it into memory

ACTIVE – High-level activation state

SUB – Detailed low-level state

DESCRIPTION – Short explanation of the service

- List all services including inactive

systemctl list-units --type=service --all

- List installed service unit files and their enablement state

[root@host ~]# systemctl list-unit-files --type=service UNIT FILE STATE arp-ethers.service disabled atd.service enabled auditd.service enabled auth-rpcgss-module.service static autovt@.service enabled blk-availability.service disabled ...output omitted...Common states in the

STATEcolumn:enabled– Starts at bootdisabled– Doesn’t start automaticallystatic– Cannot be enabled; started by dependencymasked– Completely disabled

Viewing Service Status

- To check the status of the specific service,

systemctl status <service_name>[root@host ~]# systemctl status sshd.service ● sshd.service - OpenSSH server daemon Loaded: loaded (/usr/lib/systemd/system/sshd.service; enabled; vendor preset: enabled) Active: active (running) since Fri 2025-10-24 12:07:45 IST; 2h 13min ago Main PID: 1073 (sshd) Tasks: 1 (limit: 2366) Memory: 3.4M CGroup: /system.slice/sshd.service └─1073 /usr/sbin/sshd -D Oct 24 12:07:45 host.example.com systemd[1]: Started OpenSSH server daemon. Oct 24 12:07:45 host.example.com sshd[1073]: Server listening on 0.0.0.0 port 22. Oct 24 12:07:45 host.example.com sshd[1073]: Server listening on :: port 22.Loaded: Whether the service unit file is parsed and loaded.

Active: Indicates if the service is running and for how long.

Main PID: Process ID of the main daemon.

Status Messages: Show recent service logs or events.

| Status Keyword | Meaning |

|---|---|

loaded | Unit configuration file processed. |

active (running) | Service is currently running. |

active (exited) | One-time task completed successfully. |

inactive | Service is not running. |

enabled | Service is configured to start at boot. |

disabled | Service is not configured to start at boot. |

static | Service is automatically started by another unit. |

Verifying Service State

| Command | Description | Example Output |

|---|---|---|

systemctl is-active sshd.service | Check if service is running | active |

systemctl is-enabled sshd.service | Check if starts at boot | enabled |

systemctl is-failed sshd.service | Check if failed during startup | active / failed |

systemctl --failed --type=service | List all failed services | Displays failed unit names |

Starting and Stopping Services

Services may need to be manually started or stopped for updates, configuration changes, or other administrative reasons.

Start a service:

[root@host ~]# systemctl start sshd.service

- Stop a service:

[root@host ~]# systemctl stop sshd.service

Restarting and Reloading Services

- Restart a service: stops and then starts the service (new PID assigned)

[root@host ~]# systemctl restart sshd.service

- Reload a service: applies configuration changes without changing the PID

[root@host ~]# systemctl reload sshd.service

- Reload or restart if reload not supported:

[root@host ~]# systemctl reload-or-restart sshd.service

Listing Unit Dependencies

Some services depend on others to function. Use the following commands:

List dependencies for a service:

[root@host ~]# systemctl list-dependencies sshd.service sshd.service ● ├─system.slice ● ├─sshd-keygen.target ● │ ├─sshd-keygen@ecdsa.service ● │ ├─sshd-keygen@ed25519.service ● │ └─sshd-keygen@rsa.service ● └─sysinit.target

List reverse dependencies:

[root@host ~]# systemctl list-dependencies --reverse sshd.service

Masking and Unmasking Services

Masking prevents a service from starting manually or automatically.

A disabled service can be started manually.

A masked service cannot start manually or automatically.

Mask a service:

[root@host ~]# systemctl unmask sendmail Removed /etc/systemd/system/sendmail.service.

- Unmask a service:

[root@host ~]# systemctl unmask sendmail Removed /etc/systemd/system/sendmail.service.

Enabling and Disabling Services at Boot

Enable a service to start at boot:

[root@host ~]# systemctl enable sshd.service Created symlink /etc/systemd/system/multi-user.target.wants/sshd.service → /usr/lib/systemd/system/sshd.service

- Disable a service from starting at boot:

[root@host ~]# systemctl disable sshd.service Removed /etc/systemd/system/multi-user.target.wants/sshd.service

Useful systemctl Commands

| Task | Command |

|---|---|

| View detailed unit state | systemctl status UNIT |

| Stop a service | systemctl stop UNIT |

| Start a service | systemctl start UNIT |

| Restart a service | systemctl restart UNIT |

| Reload a service configuration | systemctl reload UNIT |

| Mask a service (disable manually and at boot) | systemctl mask UNIT |

| Unmask a service | systemctl unmask UNIT |

| Enable a service at boot | systemctl enable UNIT |

| Disable a service at boot | systemctl disable UNIT |

| List dependencies of a unit | systemctl list-dependencies UNIT |

Adjusting Tuning Profiles

The tuned service optimizes system performance by applying predefined tuning profiles. These profiles adjust kernel parameters, CPU behavior, disk settings, and network tuning based on workload type.

Static Tuning

Applies predefined kernel and system settings.

Settings do not change based on system load.

Suitable for predictable workloads.

Dynamic Tuning

The tuned daemon monitors system activity.

Adjusts settings dynamically at runtime.

Useful when workloads vary (e.g., storage bursts, busy hours).

Installing and Enabling tuned

To install manually:

yum install tuned systemctl enable --now tuned

Check service status:

systemctl status tuned

Available Tuning Profiles

Tuned includes multiple profiles optimized for different workloads.

| Profile | Purpose |

|---|---|

| balanced | Default. Good balance between performance & power saving. |

| desktop | Faster response for interactive desktop workloads. |

| throughput-performance | Maximum I/O and CPU throughput. |

| latency-performance | Low-latency tuning for servers; higher power usage. |

| network-latency | Low latency for network workloads (derived from latency-performance). |

| network-throughput | Maximum network throughput. |

| powersave | Aggressive power saving. |

| oracle | Optimized for Oracle databases. |

| virtual-guest | Optimizes performance for virtual machines. |

| virtual-host | Optimizes systems acting as hypervisors. |